Exploring AI’s Powerful Expansion And Its Future Across Industries

- 6 mins read

In the complex world of international relations, alliances are often described as marriages of convenience. However, few partnerships have been as volatile, transactional, and ultimately destructive as the one between the United States and Pakistan.

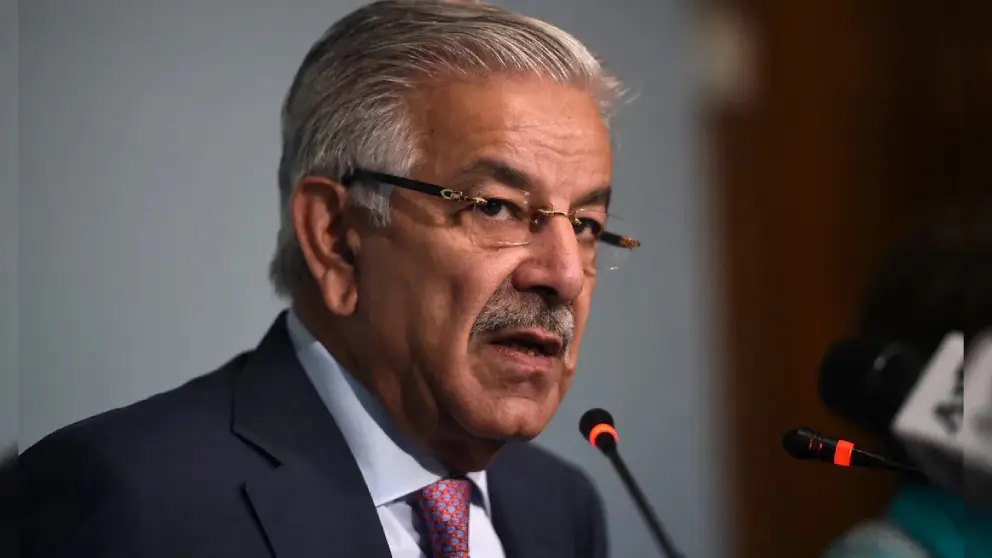

In a moment of candid frustration, Pakistan’s Defense Minister Khawaja Asif once lamented in Parliament that his country had been treated 'worse than toilet paper' by the United States. It was a harsh admission of a painful reality. for seven decades, Pakistan has repeatedly offered itself as a strategic pawn, only to be discarded the moment Washington’s objectives were met.

From the early days of the Cold War to the chaotic exit from Afghanistan in 2021, the history of US-Pakistan relations is a cyclical tale of need, greed, use, and abandonment. But as history shows, while the US was the user, the wound was largely self-inflicted.

To understand the present, we must look at the partition of 1947. Born out of the bloodshed of separation from India, Pakistan emerged as a nation deeply insecure about its larger neighbor. While India, under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, chose a path of Non-Alignment, refusing to bow to either the US or the Soviet Union, Pakistan took a different route.

Desperate for military parity with India and seeking economic aid, Pakistan’s first Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, made a pivotal decision. In 1949, he snubbed an invitation from Moscow to visit the Soviet Union, choosing instead to visit Washington.

This was the moment the die was cast. In his address to the US Congress, Liaquat Ali Khan marketed Pakistan not as an independent power, but as a bulwark against communism situated at the strategic crossroads of South Asia and the Middle East. Washington, seeking to check Soviet expansion, pounced on this desperation.

Pakistan joined American-sponsored military alliances like SEATO (1954) and CENTO (1955). The Pakistani establishment believed these pacts would protect them from India. The Americans, however, made it clear. these alliances were for anti-Soviet containment, not for settling scores in the subcontinent.

The transactional nature of the relationship became dangerously clear in the late 1950s. The CIA established a covert facility at Badaber, near Peshawar. Officially a communications center, it was actually a launchpad for U-2 spy planes to conduct reconnaissance over the Soviet Union.

On May 1, 1960, a U-2 pilot named Francis Gary Powers was shot down by the Soviets. The wreckage revealed that the flight had originated in Pakistan. The fallout was terrifying. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev famously threatened to draw a red circle around Peshawar on his maps and wipe the city out with nuclear missiles if such flights continued.

The Lesson: The US gained valuable intelligence on Soviet missile capabilities. Pakistan gained a direct nuclear threat from a superpower. It was a textbook example of an unequal exchange.

If the 1950s were about containment, the 1960s and 70s were about disillusionment. Pakistan had armed itself with American weaponry, believing it gave them an edge over India.

Islamabad realized too late that it had misread its own value. To Washington, Pakistan was a tool for global geopolitics, not a partner in regional disputes.

Pakistan did not learn from its past. In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. For the US, this was a golden opportunity to give the USSR its own Vietnam. For Pakistan’s military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq, it was a chance to secure his rule and flush the country with dollars.

Through Operation Cyclone, the CIA channeled billions of dollars in arms and funding to Afghan Mujahideen fighters, with Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) acting as the distributor.

The Cost of Victory:

While the US achieved its objective of defeating the Soviets, Pakistan paid a horrific price that it is still paying today:

There’s more to life than simply increasing its speed.

By Udaipur Freelancer

Once the Soviets withdrew in 1989, the US walked away. In 1990, invoking the Pressler Amendment, the US sanctioned Pakistan for its nuclear program the very same program Washington had conveniently overlooked when it needed Pakistan’s help against the Soviets.

History repeated itself after the horrific attacks of September 11, 2001. General Pervez Musharraf faced an ultimatum from the US, You are either with us or against us.

Once again, Pakistan became a logistics hub, this time for NATO forces in Afghanistan. Roughly 80% of NATO supplies transited through Pakistan. However, the blowback was immediate and devastating.

The nadir of the relationship came on May 2, 2011. US Special Forces raided Abbottabad and killed Osama bin Laden. The operation was conducted without Pakistan’s knowledge, a humiliating violation of sovereignty that signaled total American distrust.

The cycle concluded for now in August 2021. President Joe Biden announced the complete withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan. The subsequent Taliban takeover left Pakistan facing a security nightmare on its western border, a resurgent TTP, and an economic crisis.

Pakistani officials expressed frustration that the US was once again eating and running, achieving its narrow exit objectives while leaving Pakistan to manage the regional chaos, refugees, and terrorism fallout.

Analyzing the last 75 years reveals a consistent pattern:

The tragedy of Pakistan’s foreign policy is best highlighted by looking at its neighbor. While Pakistan was performing as a pole-dancer (to quote geopolitical analysts) for Washington, India was building its own stage.

The irony is palpable: India never tried to compete with Pakistan on Pakistan’s terms. It simply outgrew the need for dependency.

It is easy to blame the United States for being a fair-weather friend. Superpowers act in their own self-interest. that is the nature of geopolitics. The tragedy is not that the US used Pakistan, but that Pakistan made itself so readily available to be used.

Successive military and civilian leaders prioritized short-term cash flows and regime security over long-term national development. They sold their geography for rent, forgetting that when a tenant leaves, the landlord is left with the cleanup.

The question now is not whether America will abandon Pakistan again that pattern is well-established. The question is whether Pakistan will finally learn to stop offering itself up for disposal. As the old adage goes: "If you don't want to be treated like a doormat, don't lie down."

Recommended for you

Must-See Art Exhibitions Around the World This Year

The Revival of Classical Art in a Digital Age

Breaking Down the Elements of a Masterpiece Painting

The Revival of Classical Art in a Digital Age